Written by Nancy Miorelli

We normally reserve our energy for writing about insects, but we often get inquiries asking us to identify insects. This isn’t our main purpose. We’ll help you as far as we can and then refer you to other blogs, Facebook groups, and websites where entomology experts are normally lurking. Regardless, if you send us or anyone else ID requests please follow these guidelines to ensure the most refined and accurate identification.

Please don’t take this the wrong way. We *want* to help you, we’re just not qualified. Insects make up 58% of the biodiversity on the planet, with beetles alone consisting of over 350,000 species. People who study scarab beetles may not even have the expertise to help you identify your sap beetle. Joe and I are just two people, and two people just can’t know all the bugs. That’s why we refer you to places where many people with various areas of expertise are present.

But with all of that stuff out of the way, we (entomologists, enthusiasts, scientists) can only tell you what your bug is because of taxonomy.

Taxonomy is the science of classifying, organizing, and naming organisms. I can tell you that a Cardinal is a Cardinal and a Cheetah is a Cheetah because of Taxonomy.

Taxonomy is a scientific art that is being lost, but shouldn’t be. It’s one of the most important, but under appreciated, sciences of our time. Taxonomists and naturalists like Charles Darwin and Carl Linnaeus were heroes of their time. However, modern day taxonomists are struggling for both recognition and funding.

Today, I’m going to take some time here to explain what taxonomy is, how taxonomy helps us ID things, and why sometimes it’s impossible for us to know what you have.

Taxonomy In a Nutshell

Taxonomy organizes life into categories. You may recall having to memorize Kingdom, Phylum, Class, Order, Family, Genus, and Species in middle school. These are the major classification systems. Kingdom is the most broad and generally tells you what kinds of things you’re looking at. like whether it’s a plant or an animal. By time you get down to species, you know the exact organism you’re looking at. For instance, a Monarch Butterfly (Danaus plexippus) or a Five Lined Skink (Plestidon fasciatus).

While this filing system is a convenient way for us to talk about the many wondrous and beautiful things that make up this planet, the main point of taxonomy is to help us understand the story of evolution. By categorizing life, we can understand how it evolved.

Taxonomy is an amazing field that normally just gets the “naming things” tag. I’d love to go into a huge thing about how great taxonomy is, but I just don’t have the space. So you’ll have to tune in next week for a post about what taxonomists do and study.

Okay, But Why Can’t You Tell Me What My Bug Is?

There are a Lot of Bugs

There are about ~10,000 species of birds, ~5,400 species of mammals, and about ~7,400 species of amphibians. When you take a class about these organisms (ornithology, mammology, and herpetology respectively) you learn the species in the area where you’re taking the class. In my herpetology class we had to know about 100 species including reptiles and amphibians. Ornithology classes are probably similar.

Different types of beetles.

PC: Bugboy52.40 (CC by SA 3.0)

One family of beetles (Scarabs: Scarabaeidae) has over 45,000 species. There are over 350,000 named beetle species. That’s just one order out of over 30+ orders of insects. You can’t ask a bird person what the ID of a random rain forest frog is and expect them to know the answer. Asking a beetle person about a stick insect species from across the world is basically the same thing.

Family or Order Level Identification is Good Enough

All entomologists, before they reach their specialty, are well versed in knowing families of insects. These include things like House Flies (Muscidae), Weevils (Curculionidae), and Stink Bugs (Pentatomidae). We’re most likely to tell you the family that your bug is in when you ask us. This helps you because that’s where a lot of common names stop.

While cheetahs have both a common and a scientific name, many bugs just aren’t talked about enough to have a common name. Also, common names for bugs differ in different geographical regions. So, for the sake clarity, we’re likely to give you the scientific name.

Some species do have common names, but these names refer to different arthropods in different geographic regions. Therefore, using common names, even for the arthropods that have them, can cause more confusion.

These are both called red bugs. The chigger (Trombiculidae) is called a “Red Bug” in Georgia where the Apple Red Bug (Lygus mendax) is called a “Red Bug” in the North.

Generally, family level identification is enough. You can garner enough about the insect’s biology to satisfy you and know if the bug can lead to trouble. For instance, just knowing something is a type of wasp is good enough for most people. If you need more information that that, it’s best to consult an expert.

If you find a bug, and you know it’s a bug (Class: Insecta), you already know that it has six legs and has an exoskeleton. If you know that you have a beetle, you know that in addition to this, it has a shell to protect itself. If you know you have a lightning beetle (Family Lampyidae), you know that its butt lights up at night to attract mates and (maybe) you know that its larvae eat snails.

A firefly in flight.

PC: art farmer (CC by SA 2.0)

We Just Can’t Tell From Your Description or Picture

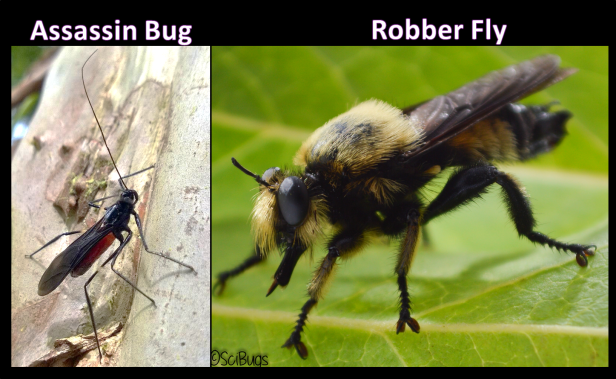

There are a lot of insects that look similar. Mimics happen frequently in insects. Flies can look like wasps, moths can look like snakes, and lots of bugs look like sticks. Mimicry helps insects survive. Telling us that your bug looks “wasp like” means that it could be a wasp, a moth, a true bug, a beetle, or a fly. At least.

Thee “wasp like” bugs above are a true bug (Hemiptera) and a fly (Diptera), respectively.

PC: Nancy Miorelli

If you have a picture, it might be too fuzzy or taken from too far away. We can easily identify other animals based on size, color, or patterns, but that stuff just doesn’t matter with insects. Insects have highly variable patterns to suit their needs. Warning coloration or camouflage are two examples where closely related species may have completely different color palettes.

Your Picture is Great! But We Can’t See the Features We Need

Many field guides can guide you to specific species. However, bugs like flies and little wasps are notoriously difficult to identify, even by experts, and you’re likely to be just told a family. Some of these problematic insects can’t be identified in the field. You need a microscope, need to dissect them, or need to submit genetic work to discern species.

In this field guide, several sharpshooters (Cicadellidae) are only listed to the genus level.

PC: Kenn Kaufman and Eric Eaton from the Kaufman Field Guide to insects of North America

There are a few exceptions. Many butterflies and dragonflies are easily recognizable for their patterns and can be identified in the field to species level.

A Seaside Dragonlet (Erythrodiplax berenice)

PC: Nancy Miorelli

Entomologists use features defined by taxonomists to identify specimens. If we ask you about these features, you probably won’t know the answers to the questions we’ll ask. How many toes (tarsi) does it have on its foot? How many segments do the antennae have? What does its eyes look like? All of these minute details are important for us to tell you what you have, and we might just not be able to know from your description or your picture.

A lot of fly identification is matching bristle patterns and thorax formations.

PC: Triplehorn & Johnson. Borror and Delong’s Introduction to the Study of Insects.

TL;DR

There are a lot of bugs. About 1 million insects have been described. We have taxonomists to thank for organizing our 1 million bugs into groups that are tangible and tell us something about the biology of the group (Beetles, Wasps, Cockroaches … etc). We’ll ID things down as far as we can for you, but generally family is as low as we can get. If you need more information, you’ll have to consult an expert.

However, before you ask us to ID anything, make sure you have a clear photo and know the location you took it. We really can’t ID things based on descriptions. Knowing the location can rule out some similar-looking contenders, but we can’t get much further than order if you don’t have a clear shot. So be brave, take that extra step closer to the bug, and ensure that we have the best possible chance of telling you what it is. Also, don’t forget to tell us where you found it =)

Thanks to Matt Zawodniak and Liz Studer for helping me edit this.

Pingback: Why is this chrysalis always dripping? | Ask an Entomologist

Pingback: So You’re In the Tropics, Named a New Species Yet? | Ask an Entomologist

Pingback: Bees carrying leaves? What’s up with that? | Ask an Entomologist